In this series of blog posts we will pick out a selection of stories from our city’s past and hopefully whet your appetite for more. You can delve deeper by visiting our website and view thousands of images at Picture Sheffield, the city’s depository of over 100,000 local images.

Chartism and the Sheffield Uprising

Chartism was a working class movement for political reform in Britain between 1838 and 1848 and the first mass working class labour movement in the world. Chartists campaigned for sweeping changes to the political system and in particular, the introduction of the Charter which consisted of six points;- Every man over 21 to have the right to vote

- A secret ballot to be introduced

- A prospective Member of Parliament (MP) should not have to own property of a certain value to become eligible to stand

- All MPs to be paid to allow working men to serve in Parliament

- All constituencies to be equal in population size

- Elections to Parliament to be held every year in order to ensure accountability to voters

Samuel Holberry and the Sheffield Chartists

Holberry was a prominent Chartist activist. After moving to Sheffield in 1835 he engaged in a number of peaceful protests.The Sheffield Working Men's Association was established in December 1837, adopting the People's Charter which stated that:

The working classes produced the rich man's wealth, while being oppressed by unjust and unequal laws.

The Association's meetings and demonstrations were well attended and peaceful, but in July 1839 local magistrates banned the gatherings. On 12 August 1839, thousands of workers and their families ignored the ban and paraded through town, finally gathering in Paradise Square, a space often used for organised public gatherings to hear speakers on an overlooking balcony. Troops were called in to break up the meeting, and a violent riot began. Around 70 demonstrators and several speakers were arrested following running battles with troops and the police.

A mass political meeting sometime in the late 19th century. The square was often used by large groups to hear public speakers. Taken from the balcony of the Middle Class School.

Membership grew after the riot and meetings and marches were held on a daily basis with regular disturbances in the town centre. After a rebellion in Newport, Monmouthshire was put down in 1839, a more radical faction of the group, known as the Chartists led by Samuel Holberry, planned an armed uprising in Sheffield. The Sheffield Chartists planned to take control of the Old Town Hall and other town centre locations while at the same time riots were to take place in Dewsbury and Nottingham. However, the conspirators were betrayed; Holberry and his colleagues were arrested, and peace restored in Sheffield.

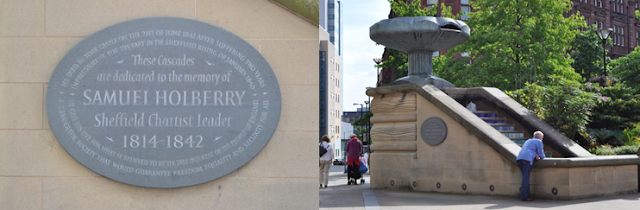

Samuel Holberry was sentenced to four years imprisonment with hard labour and died in prison at York Castle on 21 June 1842 aged 27. He is buried in Sheffield General Cemetery and remembered on a plaque in the Sheffield Peace Gardens

An account of the attempted Sheffield rising appears in a pamphlet from 1876 produced by Robert Eadon Leader, titled Reminiscences of Old Sheffield, its Streets and its People. In it, a group of men who had lived in the town in the 1840s are recorded in their conversation about the events:

According to a man named Johnson of Sheffield:

“On the 12th September, 1839, the Chartists held a silent meeting in Paradise square, which was dispersed by the soldiers and police. The Chartists reassembled in ‘Doctor's Field', at the bottom of Duke Street, where they were followed by the soldiers and police, and 36 prisoners taken.

At the Town Hall, next day, which was guarded by the dragoons, and the doors kept by policemen armed with cutlasses, I saw several anxious mothers inquiring for their missing ones. Amongst the rest was the mother of a young man who has since been an influential citizen in St. George's ward. He was tried at the assizes and acquitted.

A night or two after the Doctor's Field meeting, hearing there was to be a Chartist meeting at Skye Edge in the Park, my brother and I tried to find Skye Edge, but not succeeding, met the Chartists coming away. They marched down Duke Street, singing lustily a Chartist melody: “Press forward, press forward, There's nothing to fear, We will have the Charter, be it ever so dear…” But, alas! on turning the corner at the bottom of Duke Street, they caught sight of the helmets of the 1st Dragoons, who were coming to meet them. Instead of ‘pressing forward' we all ‘pressed' every way but that, and in two minutes not a Chartist was to be seen…”

Robert Eadon Leader, historical writer (and author of Reminiscences of Old Sheffield, its Streets and its People) and proprietor of the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent.

Margaret Gatty, the children's story writer who was married to Reverend Alfred Gatty of Ecclesfield, wrote many letters to her sister Horatia. In a letter dated 1840, she describes the recent uprising of the Chartists in Sheffield:

‘…the Chartists have been completely subdued and a dozen of them forwarded to York and I should think it very probably one or two will be hanged… they intended to have a grand display – pillaged the Town, killed the Magistrates and fired the Public Buildings – for which purposes they had got a quantity of hand grenades and other combustibles prepared…’ (31 Jan 1840)

Letter from Margaret Gatty to her sister about the Chartist uprising in Sheffield in 1840 (Sheffield Archives: With kind permission from the Hunter Archaeological Society)

Population of Sheffield in 1841 – 134,599

Tomorrow, as the industrial revolution continues apace, tension continues to rise among the working classes of Sheffield, leading to what became known as the Sheffield Outrages.